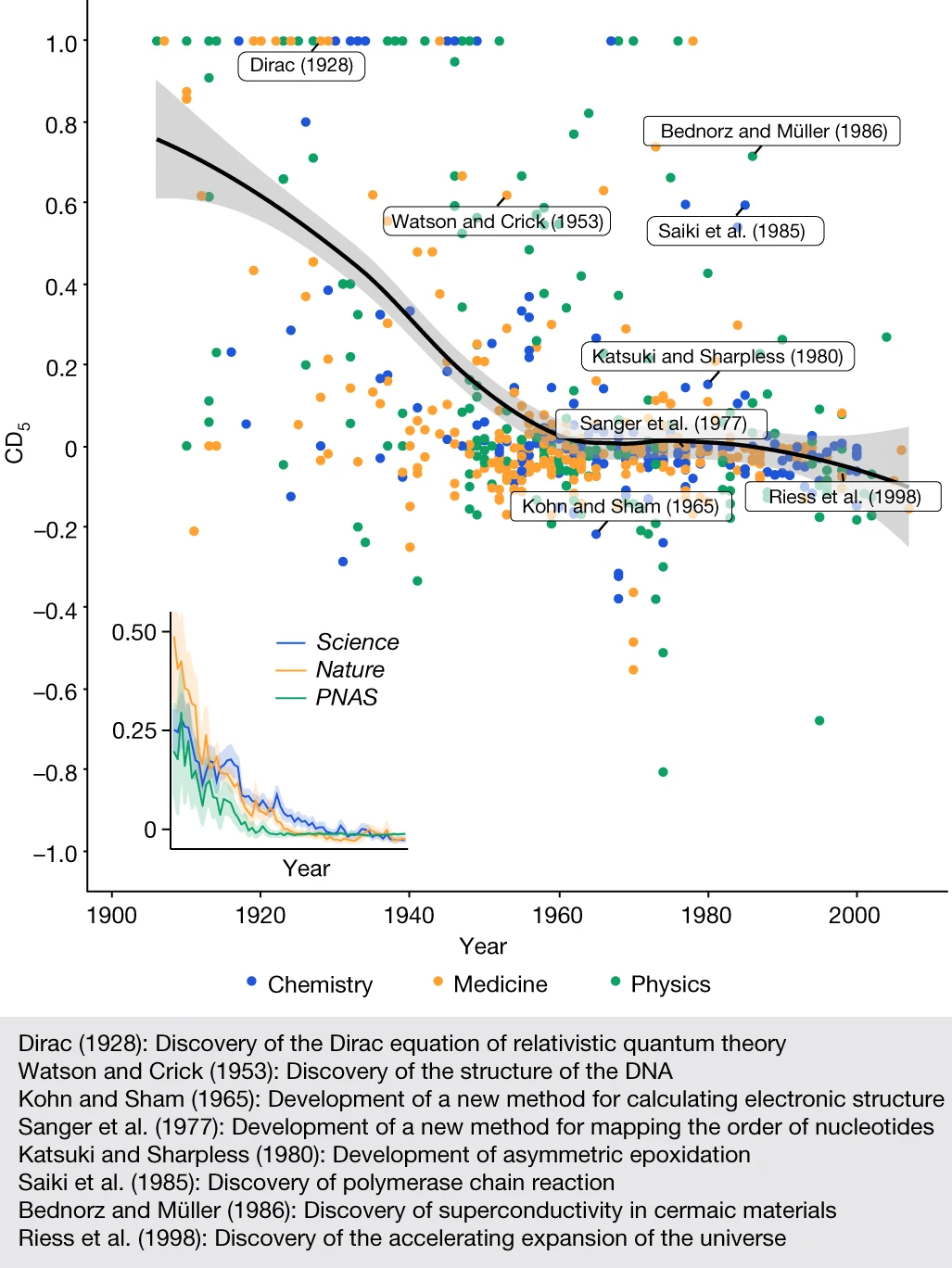

I've noticed a lot of chatter on LinkedIn and elsewhere regarding a recent Nature paper that indicates we are becoming less impactful in terms of research. In the paper, the authors provide a new metric that aims to capture how disruptive papers and patents are toward their respective fields. The metric seems to be based on whether a paper or patent changes the direction of research based on whether that work renders all previous related works absolute (i.e. no one refers to those older works anymore). The authors give examples of the proposed structure for DNA and how it made all previous works irrelevant and changed the course of research in molecular biology, genetics, and medicine. This would be considered a disruptive change. Whereas they give the other scenario of the work of Kohn-Sham and density functional theory builds upon existing knowledge and is impactful but not disruptive, as the authors seem to indicate. Using their metric, they show in figure 2, below, that the overall disruptive nature of research and technology has declined considerably in all the top-level domain groups.

Figure 2 from Park, M., Leahey, E. & Funk, R.J. Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. Nature 613, 138–144 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x

From my perspective, I'm not that surprised. I mean, I've always agreed with the age-old montage that there is very little ripe "low-hanging fruit" for picking. There are for sure problems that are ripe to solve, see the example here, but these are not "low-hanging" by any means. The authors refer to this sentiment as a potential cause as well as the exhaustive amount of research being produced that makes it difficult to keep up with, but based on their defined metric and their analysis they suggest these are not necessarily the reason for the decline. I was surprised, as my bias would suspect this is the cause, but the authors argue I am wrong. My thinking is that given we have such strong physical theories that describe much of our everyday lives, most of humankind's future advances will be in deploying and finding solutions via this understanding to address our everyday needs.

So what is the cause of the degradation in the impact our research activities are having? In the discussion part of the article, the authors indicate that their analysis points towards specialization and the narrow focus of researchers being the most likely the culprit. Hmm, I can resonate with this. I've always felt this was an issue for me, especially during and after graduate school. I've always been the kind of person who likes to learn and tinker around with any topic that piques my interest, regardless of how knowledgeable I am about that topic/field. However, I've quickly found that as a society we don't want that anymore, or at least that's how I feel. We want "experts" and "specialists", whatever those are.

If we think about it, what made the early 20th century so productive, as shown in figure 5 of the nature paper. My opinion on this is that most academics and industry lab researchers worked on so many different topics across physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering. Let's start with arguably the most famous physicist of the early 20th century, Albert Einstein. Early on he worked on improving fundamentally our understanding of

kinetic theory. Then he went on to basically seed all of the quantum theory with his

theory of light-matter interactions. Finally, he wanted to better describe our understanding of time and space so he codified

special relatively and then gave us a more general version of it that included gravity, i.e.,

general relativity. I assume he is not the exception during this era but the norm as many physicists seemed to have worked on anything that needed answering and was of interest to them. I believe

Enrico Fermi was like this, and so was

Freeman Dyson.

Figure 5 from Park, M., Leahey, E. & Funk, R.J. Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. Nature 613, 138–144 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x

So who is doing this now, maybe a handful of physicists? I don't know, but I do know that specialization is the norm and is expected. In my mind, it seems, clear what we need to do: encourage broad interest and application of skills and knowledge towards any area where a new paradigm, improved understanding, or novel technology would be disruptive. The authors put it in the following form:

"Even though philosophers of science may be correct that the growth of knowledge is an endogenous process—wherein accumulated understanding promotes future discovery and invention—engagement with a broad range of extant knowledge is necessary for that process to play out, a requirement that appears more difficult with time. Relying on narrower slices of knowledge benefits individual careers[53], but not scientific progress more generally."

So next time someone asks me what my domain or technical expertise is, I'm going to say "I think, create, and solve"

Reuse and Attribution

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please refrain from using ad hominem attacks, profanity, slander, or any similar sentiment in your comments. Let's keep the discussion respectful and constructive.